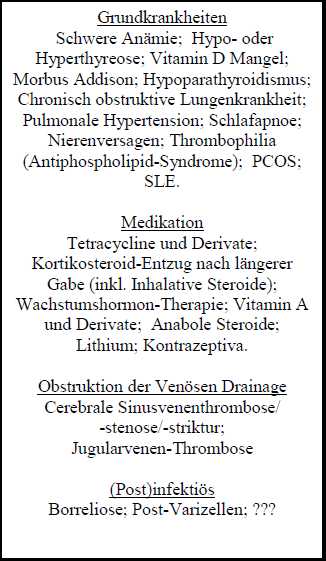

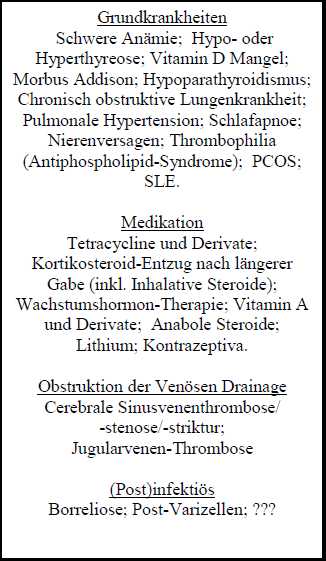

The international nomenclature distinguishes idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) from secondary pseudotumor cerebri. In the latter case, there is evidence of an underlying cause (drugs, certain diseases) (Ball and Clarke, 2006).

Although the pseudotumor cerebri was first described in 1897, the pathophysiology is still largely unknown.

But there are some known risk factors that obviously contribute to the development of PTC.

In postpubertal and adult patients obesity and female sex are known risk factors. In contrast, within the group of prepubertal patients this is not the cases pointing to a different underlying pathophysiology in this age group.

Secondary Pseudotumor cerebri

There is growing evidence that the strict differentiation between idiopathic and secondary intracranial hypertension is artificial. After a thorough diagnostic work-up, an underlying diseases or condition which may be a possible causal factor or co-factor is found in a relatively high percentage of affected children. However, causality is often not easy to prove.

Secondary causes:

Symptoms

Symptoms of idiopathic intracranial hypertension ( = pseudotumor cerebri ) are often non-specific, which commonly leads to delayed diagnosis. Typical symptoms are dependent on age . Moreover, especially in children, patients can be completely symptom free early in the course of the disease. There are, however, alarming signs that should always raise the suspicion

Red flag symptoms are

:

1 ) unexplained abducens paresis

2 ) unexplained papilledema

3 ) chronic daily headaches, especially with nocturnal headache with an unremarkable MRI and then papilledema on eye exam.

4) Pulsatile tinnitus

School age, teenager

– Incidental finding

– Headache (chronic daily headache, migraine like headache)

– Visual defects (blurred vision,

double vision)

– Nausea/vomiting

– Tinnitus, pulsatile |

Infancy (can be as young as 6 months!)

– Incidental finding

– unspecific

– Irritability

– Apathy/Somnolence

– »Strabismus« |

Diagnostic work-up

For a proposal of a structured diagnostic work-up see this ppt file.

If PTC is suspected, the first step ist to confirm the diagnosis and exclude differential diagnoses.

1) Neuroophthalmology:

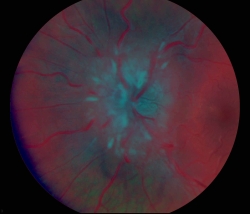

- Documentation of papilledema (Photo documentation !!)

- A pseudo-papilledema (as Drusenpapille) must be excluded (helpful for differentiation: ultrasound, OCT, fluorescein angiography).

- Check for sixth nerve palsy, visual acuity, visual field defects (typically enlargement d blind spot and inferior nasal visual field defects; usually not noted by patients). Check colour vision..

- Some authors recommend testing of "contrast sensitivity" (for example, Pelli-Robson test). In one study 50% of PTC patients showed abnormalities of contrast sensitivity (Wall & George 1991)

- The value of VEP testing is controversial. VEP are typically normal in PTC patients. If abnormal, think of differential diagnosis, mainly inflammatory CNS diseases.

- Optic Coherence Tomography (OCT) is increasingly used by ophthalmologists. Results of recent studies in patients with pseudotumor cerebri are inconsistent, but encouraging. Recently there has been great progress with more sophisticated OCT techniques, which likely will become part of the routine work-up of PTC patients.

For review:

•Optical Coherence Tomography in Papilledema: What Am I Missing? Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology 2014;34(Suppl):S10 – S17

doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000162

After objectification of the ophthalmologic findings, neuroimaging is mandatory.

- MRI / Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- MR venography (Caution: Sino-venous thrombosis!)

In recent years, the significance of the MRI scan has increased. Along with improved resolutions and techniques more indirect imaging signs of intracranial pressure have been identified. These can assist with establishing the diagnosis (partial "empty sella", "flattening of the posterior globes", "sinouvenous thrombosis" . ..).

Unfortunately, non-invasive MRI techniques to determine the intracranial pressure are still not available for routine use..

After imaging, a standardised LP to measure the CSF opening pressure is crucial

(Patient lateral position, with legs only slightly flexed, as relaxed as possible, or, preferred my some, always sedated).

Sedative or analgetic drugs know to potentially increase the intracranial pressure should be avoided (mainly ketanest).

Although the role of ketamine is controversial, it is our own clinical impression that falsely elevated opening pressure measurements occur relatively often when sedation is done with ketamine.

Hypercapnia should be measured when LP is done under anesthesia. Unfortunately, there is not a single way to sedate patients without potentially altering of the intracranial pressure.

The same applies to insufficient sedation, where the pressure can be falsely high due to pain, fear, screaming / crying.

This is an unsolved diagnostic dilemma and considerably limits the reliability of pressure measurement done during a LP!!!

The "normal" opening pressure in children is not age-dependent and is higher than has been suggested previously in pediatric text books. In a phantastic talk given at the 2012 Annual Meeting of the German Society of Pediatric Neurology Robert Avery presented and discussed the results of his seminal study on reference values of CSF opening pressure in children.

28 cm H2O has now to be considered the upper limit of normal in children.

Although there where some data to suggest that this limit may be different if the child is obese/non-obese or sedated/non-sedated, I personally always apply 28 cm as the upper limit in order to prevent unneccessary confusion with parents and colleagues. .

IMPORTANT: It can not be stressed often enough that a single opening pressure measurement does never exclude nor confirm the diagnosis of PTC!!! Pressure values always have to be interpreted with caution and in the whole clinical context of history, signs, symptoms, treatment response, and so on. Even a healthy child can have an opening pressure above 40 cm H2O! Contrary, an opening pressure below 28 cm has been desribed in clear PTC cases.

Frequently encountered mistakes

It is my experience, confirmed by many other experts in the field, that the diagnosis of PTC is not always established in a methodologically correct manner, especially in children. This statement is based on my own experience of the treatment of well > 150 pediatric PTC patients, many of which were mistreated when referred to our clinic..

Common mistakes:

1) Diagnosis:

One of the most common mistakes is that the diagnosis is made although the diagnostic criteria (modified Dandy criteria; Friedman criteria) are not met:

- CSF is not normal (especially: increased cell count). In this case, the diagnosis pseudotumor cerebri can not be made and the search for a secondary cause should be intensified. A variety of infections and non-infectious inflammatory CNS diseases are associated with increased intracranial pressure.

- Cerebral imaging is not normal. Cases of a clear hydrocephalus have been reported to us as pseudotumor cerebri.

The role of sinouvenous stenosis in making the diagnosis of PTC is still unclear. But MRV should always be done, in a perfect world before and after LP because stenosis might resolve after LP. Only bilateral stenosis of the transverse sinus is relevant..

- The papilledema is not a papilledema. This is probably the most common cause for false diagsosis of PTC. After cases with presumed papilledema have been re-checked in a tertiary ophthalmology center, papilledema often turns out to be pseudopapilledema, including drusen. Therefor, re-check eye exam BEFORE doing a diagnostic lumbar puncture, which is most certainly traumatic, at least for some children!

A pseudotumor cerebri without papilledema (IIHWOP) seems to exist in children as well. However, in these cases, the diagnosis should be critically questioned!

Differential diagnosis of papilledema:

adopted from "Neuro-Ophthalmology" von Liu, Volpe, Galetta (s.o.). – Opticus Neuropathie (Opticus Neuritis; Ischämische Opticus Neuropathie)

Klinik: typischerweise plötzlicher Beginn, oft einseitig, afferentes Pupillendefizit, gestörtes Farbsehen

- Pseudopapillenödem

Ophthalmologischer Befund: stabil über die Zeit bei Kontrollen, anomale retinale Vaskulatur, irregulärer Papillenrand, spontane venöse Pulsationen, unter anderem. Fluorescein Angiographie!

Gesichtsfelddefekte sind möglich!

In der Differentialdiagnose ist besonders bei einseitigen Befunden eine ausgeprägte Weitsichtigkeit (Hyperopie, Hypermetropie) ursächlich möglich.

- Drusen

Calciumablagerungen im Nervenkopf, meist ab Ende erste Dekade des Lebens erkennbar. Oft assoziiert mit anomalen retinalen Arterienverzweigungen.

Im CT möglicherweise darstellbar

– Inflammation (z.B. Uveitis)

– Optic disc tumors (z.B. M. Hippel Lindau; Tuberöse Sklerose), wegen übriger Klinik Verwechslung sicher unwahrscheinlich

– Leber`sche Amaurose

- u.v.m.

|

Phänomene eines Papillenödems (Stauungspapille)

– eine frühe Stauungspapille zeigt sich typischerweise superior und inferior, im Verlauf dann nasal und zuletzt auch temporal.

– typischerweise braucht die Entstehung einer Stauungspapille 1-5 Tage, sehr selten (z.B. bei Subarachnoidalblutung) auch innerhalb Stunden.

– venöse Stase und Dilatation, ggf. Mikroaneurysmen, peripapilläre radiale Blutungen.

– "Cotton wool spots" (High grade, floride Stauungspapille) – Verschwinden spontaner venöser Pulsationen (wenn vorhanden kann der Druck als < 18 cm H2O angesehen werden). Cave: können bei 10% der Gesunden mindestens einseitig Fehlen!

– Meist ist das Ausmass des Papillenödems bds. gleich, aber asymmetrisch und rein einseitige Stauungspapillen kommen vor!

– Cave: interindividuelle Unterschiede des Papillenödems bei gleichen Hirndrücken können eindrucksvoll sein. Ergo: das Ausmass der Stauungspapille ist kein guter Indikator für die Höhe des Druckes!

– Chronisches Papillenödem: "Champagner Korken"-Erscheinung, Pseudodrusen, Disk-Atrophie, venöse Kollateralgefässe, Neovascularisation subretinal.

BEHANDELTE STAUUNGSPAPILLE

Die Erholung dauert typischerweise Wochen, auch Monate sind möglich. Eine gewisser Anteil der Patienten hat eine Rest-Stauungspapille noch Jahre trotz normalem intrakraniellen Druck!

|

- CSF opening pressure falsely high, e.g. due to inadequate sedation or inadequate relaxation of the patient. Unskilled LP can also be a reason. .

Unfortunately, effects of drugs used for sedation or analgesia, on the other hand, can also alter intracranial pressure leading to false results.

This is an unsolved diagnostic dilemma!

- Diagnosis is based an wrong reference data: In children > 1 year of age, 28 cm H2O should now be the upper limit of normal.

NOTE: An single opening pressure measured during a single LP is always and only a snapshot which, taken alone, is never diagnostic nor exclusive.

|

Therapy

There is not a single clinical treatment trial on pseudotumor cerebri in children. Therefore, therapy follows expert opinions and decades of experience.

The following question are controversial and inconsistently addressed in different centres in the world, or even within one country:

- When should therapy be initiated?

- What is the drug of first choice?

- What dosage is targeted?

- How long should we treat?

- How do we best monitor treatment success?

- When should treatment be escalated?

- When is surgery indiated?

Treatment goals are:

1) preventing persistent visual disturbances

2) improve headache

3) prevent unnecessary invasive procedures

Based on currently available literature and on my own experience , I have created the following guideline ,which is only a rough orientation. This is NOT a "recipe "!! Every single case is different and individual treatment decisions are often necessary. .

In treatment - resistent or other difficult cases you should contact specialist with broad expience in the managment of pediatric PTC patients!

SOP as pdf

The first therapeutic step is always to lower the pressure through the diagnostic lumbar puncture ( LP ).

Measure the closing pressure as well!

Sometimes considerable amounts of CSF need to be drained to achieve a closing pressure of < 20 cm H2O .

|

Some authors have suggesed a severity adapted treatment approach

( for example, Liu et al., fantastic book : Neuro- Ophthalmology , Diagnosis and Management , Saunders , Elsevier )

treatment decisions should not rest on ... the severity of papilledema , or CSF opening or closing pressure . Instead , the modern management of pseudotumor cerebri is based largely upon the level of visual loss . From Liu et al. |

The following recommendation is a very useful orientation:

1. No visual loss:

symptomatic headache (migraine) therapy

weight reduction

if necessary Acetazolamide

2. Mild visual loss:

Acetazolamide

Furosemide

(im Text wird auch Topiramat empfohlen als 3.Alternative)

Weight reduction, if necessary

3. Severe, or progression of visual loss:

Optic nerve sheath decompression

High-dose IV steroids and acetazolamide

Lumboperitoneal shunt for failed ONSD or intractable headache

Addition: sinovenous stents must be considered highly experimental in childhood!

Problems

The following issues can be frequently observed in second opinion cases, referred as "treatment resistant PTC"::

- Insufficient dose of acetazolamide. There is a common hesitance to increase the dose. Given the lack of any scientific basis for the use of alternative medication, I always recommend to increase the dose until side-effects of acetazolamide are not tolerated any more. The recent NORDIC trial (see literature) concluded that high dose (in adults up to 2 g/d) acetazolamide is usually well tolerated and efficient, at least to improve vision.

- Misinterpretation of the course of papilledema.A significant reduction of the severity of papilledema may only be evident with a delay of weeks or even months. Even more important, papilledema is often not getting back to "normal". A slight prominence of the papilla can be seen in a significant proportion of PTC patients, even after years of remission, with no indication of any visual disturbances. This is therefore not an indication for a change in therapy or treatment escalation as long as the rest of the neuroophthalmology exam is still normal.

- CSF opening pressure measurements are repeatedly done on follow-up to objectify whether treatment is efficient.

This is usually NOT indicated and often misleading, usually towards over-treatment!

Given the lack of standardisation (e.g. sedation) and multiple confounders to be considered, I usually DO NOT recommend follow-up LP, unless there are signs (mainly ophthalmology) or symptoms strongly suggesting treatment resistance or relapse.

- Headache is misinterpreted as treatment resistance. This is particularly common and has even lead to unnessecary shunt operations!

Many IIH patients have persistent headaches, even after normalization of the intracranial pressure

Patients with IIH frequently have headaches not necessarily related to increased intracranial pressure |

But: some cases are really tricky. Telemetric continious intracranial pressure measurements may then be indicated to get more than a snapshot value.

In general, headache clinics should be closely involved in the management of PTC patients whenever headache is a main complaint.

- Premature discontinuation of therapy.

We usually treat for at least 4-6 months. After the Duesseldorf observation of relapses in more than 20% of cases, follow-up is now recommended for at least two years at specialised centers.

- Drug adherence.

Especially in adolescents, drug adherence can be an important issue that has been linked to poorer outcome in this particular age group!

A negative base excess of around -9 mmol/l is usually expected in patients on normal doses of acetazolamide, provided they take their medication.

- Invasive treatment when it is not indicated.

This is an important but also very complicated issue. Based on my personal experience my main message at this point is, however, that PTC is usually not a surgical disease!!

In our center we have prevented a large number of patients from getting surgery, in none of them this resulted in adverse outcome!

Of course, in rare cases of fulminant PTC with very rapid loss of vision, and cases where there are signs of visual deterioration on follow-up, the operation can still be indicated even as an urgent procedure!!

However, before considering surgery, question your diagnosis (!), objectify findings from ophthalmology, consider pressure monitoring, consider drug adherence problems, and, above all, have interdisciplinary discussions!!

Personal experience: serial LP can prevent surgery in some cases, where it had initially been started as a bridging therapy before surgery and finally led to long-lasting remission, thus, preventing surgery..

Prognosis

Without sufficient treatment, permanent visual impairment can occur, ranging from mild visual loss, disturbed color vision, impaired contrast sensitivity, visual field defect to permanent blindness. Severe visual impairment can occur as early as at presentation. More commonly it develops over the course of weeks or months, which can happen even under therapy, or as a consequence of a relapse!.

However, provided the patient is managed in close collaboration with the treating pediatrician, child neurologist, ophthalmologist, neurosurgeon, and radiologist, permanent visual impairment can be prevented without invasive treatment in > 90% of cases (personal experience).

"Optimal management of IIH requires good communications between specialties to protect the patient from unnecessary lumbar punctures and CSF diversion surgery on the one hand and avoidable visual loss on the other."

Standridge SM. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension in children: A review and algorithm. Pediatr Neurol 2010;43:377 - 390

|

Future

There may be a place for specialised, tertiary PTC clinics for children. It is also hoped by the author of this website that international collaborations will start, in order to achieve an internationally accepted consensus on guidelines and standards leading to the best possible management for our young PTC patients.

ESPED Erhebung

Results of the nations-wide surveillance of pediatric PTC in Germany.

(contact the author for a copy of this or other papers)

Literatur

Selected articles on Pseudotumor cerebri

2019

2015 und 2016

Fisayo A, Bruce BB, Newman NJ, Biousse V . Overdiagnosis of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology . 2016 Jan 26;86(4):341-50.

Cartwright C, Igbaseimokumo U. Lumbar puncture opening pressure is not a reliable measure of intracranial pressure in children. J Child Neurol. 2015 Feb;30(2):170-3.

Narula S, Liu GT, Avery RA, Banwell B, Waldman AT. Elevated cerebrospinal fluid opening pressure in a pediatric demyelinating disease cohort.Pediatr Neurol. 2015 Apr;52(4):446-9.

Krishnakumar D, Pickard JD, Czosnyka Z, Allen L, Parker A. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension in childhood: pitfalls in diagnosis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2014 Aug;56(8):749-55.

Headache and PTC. A largely neglected topic!!!:

Ducros A, Biousse V . Headache arising from idiopathic changes in CSF pressure. Lancet Neurol . 2015 Jun;14(6):655-68.

Über die Pathophysiologie des Pseudotumor cerebri. Beim Lesen dieser Artikel darf nicht vergessen werden, dass hier fast immer die erwachsenen Form diskutiert wird!

Markey KA 1 , Mollan SP 2 , Jensen RH 3 , Sinclair AJ 4 . Understanding idiopathic intracranial hypertension: mechanisms, management, and future directions. Lancet Neurol 2016 Jan;15(1):78-91.

2014

•Optical Coherence Tomography in Papilledema: What Am I Missing?

Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology 2014;34(Suppl):S10 – S17

doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000162

Avery RA . Neuropediatrics. 2014, 45:206-11. Reference range of cerebrospinal fluid opening pressure in children: historical overview and current data.

NORDIC Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Study Group Writing Committee, Wall M, McDermott MP, Kieburtz KD, Corbett JJ, Feldon SE, Friedman DI, Katz DM, Keltner JL, Schron EB, Kupersmith MJ. Effect of acetazolamide on visual function in patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension and mild visual loss: the idiopathic intracranial hypertension treatment trial.. 2014 Apr 23-30;311(16):1641-51.

Babiker MO, Prasad M, MacLeod S, Chow G, Whitehouse WP. Fifteen-minute consultation: the child with idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed . 2014 Oct;99(5):166-72

Liu B, Murphy RK, Mercer D, Tychsen L, Smyth MD. Pseudopapilledema and association with idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Childs Nerv Syst. 2014 Jul;30(7):1197-200.

McGeeney BE, Friedman DI. Pseudotumor cerebri pathophysiology. Headache. 2014 Mar;54(3):445-58.

2013

Tibussek D , Distelmaier F, von Kries R, Mayatepek E. Pseudotumor cerebri in childhood and adolescence -- results of a Germany-wide ESPED-survey. Klin Padiatr. 2013;225:81-5.

2012

2011

Review: Cerebral venous sinus system and stenting in pseudotumor cerebri

Is cerebrospinal fluid shunting in idiopathic intracranial hypertension worthwhile? A 10-year review.

"Conclusion: We suggest that CSF shunting should be conducted as a last resort in those with otherwise untreatable, rapidly declining vision. Alternative treatments, such as weight reduction, may be more effective with less associated morbidity."

Is the brain water channel aquaporin-4 a pathogenetic factor in idiopathic intracranial hypertension? Results from a combined clinical and genetic study in a Norwegian cohort.

Continuous intracranial pressure monitoring: a last resort in pseudotumor cerebri.

Pseudotumor Cerebri: Brief Review of Clinical Syndrome and Imaging Findings.

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: lumboperitoneal shunts versus ventriculoperitoneal shunts--case series and literature review.

The syndrome of pseudotumour cerebri and idiopathic intracranial hypertension.

Pseudotumor cerebri. (Child Nervous System)

2010

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension in children: a review and algorithm.

Use of optical coherence tomography to evaluate papilledema and pseudopapilledema.

Pediatric idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri). FREE FULLTEXT

An update on idiopathic intracranial hypertension.

Continuous intracranial pressure monitoring in pseudotumour cerebri: Single centre experience.

Advancement in idiopathic intracranial hypertension pathogenesis: focus on sinus venous stenosis.

Incidence of papilledema and obesity in children diagnosed with idiopathic ''benign'' intracranial hypertension: case series and review. FREE FULLTEXT

Clinical spectrum of the pseudotumor cerebri complex in children. Kontaktieren Sie den Autor für eine Kopie

Ältere Artikel

Review 2007 aus Cephalgia

State of the art (2002 review von Friedman and Jacobson) Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension

Cochrane Review: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 Jul 20;(3):CD003434.

Interventions for idiopathic intracranial hypertension.

Leitlinie der DGN (nicht 1:1 für Kinder anzuwenden!)

Diagnostic criteria, Neurology 2002

Intracranial hypertension foundation

Historisch: The Production of Cerebrospinal Fluid in Man

and Its Modification by Acetazolamide

Grundlagen: Der Subarachnoidalraum des menschlichen N. Opticus (engl.)

Grundlagen: THE BOWMAN LECTURE

PAPILLOEDEMA: 'THE PENDULUM OF PROGRESS'

Grundlagen: The Importance of Lymphatics in Cerebrospinal Fluid Transport

Historisch: Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Without Papilledema

Books

Great Overview (2007)t:

Historical overview 1991:

Great:

Historical overview 1978:

Der Autor

|

|

Publications Tibussek D

Boles S, Martinez-Rios C, Tibussek D, Pohl D. Infantile Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension: A Case Study and Review of the Literature. J Child Neurol. 2019 Nov;34(13):806-814. doi: 10.1177/0883073819860393.

Tibussek D, Ghosh S, Huebner A, Schaper J, Mayatepek E, Koehler K."Crying without tears" as an early diagnostic sign-post of triple A (Allgrove) syndrome: two case reports. BMC Pediatr. 2018 Jan 15;18(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s12887-017-0973-y.

Tibussek D, Rademacher C, Caspers J, Turowski B, Schaper J, Antoch G, Klee D. Gadolinium Brain Deposition after Macrocyclic Gadolinium Administration: A Pediatric Case-Control Study. Radiology. 2017 Jun 21:161151.

Kunstreich M, Kreth JH, Oommen PT, Schaper J, Karenfort M, Aktas O, Tibussek D, Distelmaier F, Borkhardt A, Kuhlen M. Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis with SOX1 and PCA2 antibodies and relapsing neurological symptoms in an adolescent with Hodgkin lymphoma. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2017 Jul;21(4):661-665.

Tibussek D, Klepper J, Korinthenberg R, Kurlemann G, Rating D, Wohlrab G, Wolff M, Schmitt B.Treatment of Infantile Spasms: Report of the Interdisciplinary Guideline Committee Coordinated by the German-Speaking Society for Neuropediatrics. Neuropediatrics. 2016 Jun;47(3):139-50.

Tibussek D, Distelmaier F, Karenfort M, Harmsen S, Klee D, Mayatepek E.Probable pseudotumor cerebri complex in 25 children. Further support of a concept. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2017 Mar;21(2):280-285.

Wolf NI, Vanderver A, van Spaendonk RM et al., 4H Research Group. Clinical spectrum of 4H leukodystrophy caused by POLR3A and POLR3B mutations. Neurology 2014;83:1898-905

Prestel J, Volkers P, Mentzer D, Lehmann HC, Hartung HP, Keller-Stanislawski B; GBS Study Group. Risk of Guillain-Barré syndrome following pandemic influenza A(H1N1) 2009 vaccination in Germany. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23:1192-204

Borusiak P, Langer T, Tibussek D, Becher T, Jenke AC, Cagnoli S, Karenfort M. YouTube as a source of information for children with paroxysmal episodes. Klin Padiatr . 2013 Dec;225(7):394-7

Tibussek D , Distelmaier F. Klinik, Diagnostik und Therapie der idiopathisch intrakraniellen Hypertension im Kindesalter. Ein Update. Neuropädiatrie in Klinik und Praxis 2013

Tibussek D, F. Distelmaier F, von Kries R, E. Mayatepek E. Pseudotumor Cerebri in Childhood and Adolescence - Results of a Germany-wide ESPED-survey. Der Pseudotumor cerebri im Kindes- und Jugendalter - Ergebnisse einer Deutschland-weiten ESPED-Studie. Klin Padiatr 2013; 225(02): 81-85.

Tibussek D , Distelmaier F. Klinik, Diagnostik und Therapie der idiopathisch intrakraniellen Hypertension im Kindesalter. Ein Update. Neuropädiatrie in Klinik und Praxis 2013 (in press).

Tibussek D, F. Distelmaier F, von Kries R, E. Mayatepek E

Pseudotumor Cerebri in Childhood and Adolescence - Results of a Germany-wide ESPED-survey

Der Pseudotumor cerebri im Kindes- und Jugendalter - Ergebnisse einer Deutschland-weiten ESPED-Studie.

Klin Padiatr 2013; 225(02): 81-85.

Rostasy K, Mader S, Schanda K, Huppke P, Gärtner J, Kraus V, Karenfort M, Tibussek D, Blaschek A, Bajer-Kornek B, Leitz S, Schimmel M, Di Pauli F, Berger T, Reindl M. Anti-Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibodies in Pediatric Patients With Optic Neuritis. Arch Neurol. 2012

Poretti A, Vitiello G, Hennekam RC, Arrigoni F, Bertini E, Borgatti R, Brancati F, D'Arrigo S, Faravelli F, Giordano L, Huisman TA, Iannicelli M, Kluger G, Kyllerman M, Landgren M, Lees MM, Pinelli L, Romaniello R, Scheer I, Schwarz CE, Spiegel R, Tibussek D, Valente EM, Boltshauser E. Delineation and Diagnostic Criteria of Oral-Facial-Digital Syndrome Type VI. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012; 11;7:4.

Tibussek D, Distelmaier F, Kummer S, von Kries R, Mayatepek E. Sedation of children during measurement of CSF opening pressure. Lack of standardisation in German children with pseudotumor cerebri. Klin Padiatr. 2012;224:40-2

Koy A, Freynhagen R, Mayatepek E, Tibussek D. Hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy with autonomic crises: a Turkish variant of familial dysautonomia? J Child Neurol. 2012;27:191-6.

Mall S, Buchholz U, Tibussek D , Jurke A, an der Heiden M, Schweiger B, Diedrich S, Alpers K. A large outbreak of influenza B-associated benign acute childhood myositis in Germany, 2007/2008. Pediatr Infect Dis J

2011; 30:e142-6.

Allen NM, Tibussek D , Borusiak P, King MD

Benign tonic downgaze of infancy .

Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2010; 95:F372.

Kummer S, Schaper J, Mayatepek E, Tibussek D . Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome in Early Infancy . Klin Padiatr 2010; 222:269-70.

Tibussek D , Distelmaier F, Schneider DT, Vandemeulebroecke N, Turowski B, Messing-Juenger M, Willems PHGM, Distelmaier F, Mayatepek E Clinical spectrum of the pseudotumor cerebri complex in children . Child Nerv Syst 2010; 26:313-21.

Tibussek D , Hübsch S, Berger K, Schaper J, Rosenbaum T, Mayatepek E. Infantile onset neurofibromatosis type 2 presenting with peripheral facial palsy, skin patches, retinal hamartoma and foot drop . Klin Padiatr. 2009;221:247-50.

Karenfort M, Kieseier BC, Tibussek D , Schaper J, Mayatepek E. Rituximab as a highly effective treatment in a female adolescent with severe multiple sclerosis . Dev Med Child Neurol 2009; 51:159-61.

Sabir H, Mayatepek E, Tibussek D . Rhythmische Lidbewegung beim Kauen und kongenitale Ptosis . Monatsschr Kinderheilkd 2009

Siehe auch hier

Tibussek D , Distelmaier F, Mayatepek E. Pseudotumor cerebri (Syn.: Die pädiatrische idiopathische intrakranielle Hypertension) Symptomatik, Diagnostik, Therapie. Review. Päd (2009)

Schmitt B, Hübner A, Klepper J, Korinthenberg R, Kurlemann G, Rating D, Tibussek D , Wohlrab G, Wolff M: Therapie der Blitz-Nick-Salaam-Epilepsie Neuropädiatrie in Klinik und Praxis , 2009; 4: 92-116

Sabir H, Mayatepek E, Schaper J, Tibussek D . Baby-walkers: an avoidable source of hazard. Lancet. 2008;372:2000

Tibussek D, Rosen A, Langenbach J, Mayatepek E. Acute onset toe walking. Video documentation of "benign acute childhood myositis". Mov Disord. 2008 30;23:2104-5. Das Video dazu.

Stienen A, Weinzierl M, Ludolph A, Tibussek D , Häusler M. Obstruction of cerebral venous sinus secondary to idiopathic intracranial hypertension . Eur J Neurol. 2008;15:1416-8.

Distelmaier F, Mayatepek E, Tibussek D . Probable idiopathic intracranial hypertension in pre-pubertal children. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:356-7.

Weber C, Schaper J, Tibussek D , Adams O, Mackenzie CR, Dilloo D, Meisel R, Göbel U, Laws HJ. Diagnostic and therapeutic implications of neurological complications following paediatric haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;41:253-9.

Tibussek D , Karenfort M, Mayatepek E, Assmann B. Clinical reasoning: shuddering attacks in infancy. Neurology. 2008 25;70:e38-41.

Distelmaier F, Tibussek D , Schneider DT, Mayatepek E. Seasonal variation and atypical presentation of idiopathic intracranial hypertension in pre-pubertal children. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:1261-4.

Tibussek D , Wohlrab G, Boltshauser E, Schmitt B (2006) Proven startle provoked epileptic seizures in childhood:semiological and electrophysiological variability. Epilepsia. 2006;47:1050-8 .

Tibussek D , Mayatepek E, Distelmaier F, Rosenbaum T (2006) Status epilepticus due to attempted suicide with isoniazid. Eur J Pediatr. 165(2):136-7.

Tibussek D , Distelmaier F, Schonberger S, Gobel U, Mayatepek E. (2006) Antiepileptic treatment in paediatric oncology--an interdisciplinary challenge. Klin Padiatr. 218(6):340-9.

Iff T, Meier R, Olah E, Schneider JFL, Tibussek D , Berger C (2006) Tick-borne meningo-encephalitis in a 6-week-old infant. Eur J Ped 164(12):787-8.2

Tibussek D , Meister H, Walger, M, Foerst, A, von Wedel, H (2002) Hearing Loss in Early Infancy Affects the Maturation of the Auditory Pathway. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 44: 123-129 .

Yours

Dr. Daniel Tibussek

up